In mainland China, where I lived from 1999 to 2010, school children enjoy a month-long Lunar New Year holiday. Because I worked in a school during those years, I always traveled during that time. I lived in Beijing, which was then home to millions of rural migrant laborers, and each year when the New Year rolled around, the migrants headed out of town—they were going home to spend the holidays with their families in small villages all over the country. I usually headed to either Yunnan or Guizhou, both mountainous provinces in the southwest, where I too would spend time in villages that bustled with the excitement of sons and daughters returning home for the holidays. In the villages, envious residents listened to the urban tales of their returned neighbors who had left their homes to work on construction sites, in restaurants, and in factories in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Dongguan, earning the equivalent of $100, $150, even $200 a month—at that time an unimaginable amount for farmers in the mountainous villages of southwest China. I knew that in the big cities of China these migrant laborers were members of an underclass, looked down upon by their urban compatriots who drove Japanese, Korean, and German cars and lived in three bedroom, heated highrise apartments or villas in gated communities. It is estimated that in the decade of the 2000’s, some 150 million rural Chinese left their villages and moved to cities in search of work—the biggest mass movement of human beings in history. These people fueled China’s then double digit economic growth rates for some 30 years. And every year, as the Lunar New Year approached, millions and millions of them crammed into trains and buses, leaving their city jobs behind to journey back home—the only chance they had all year long to see their family members and friends. Every year the villages had more TVs, more motorcycles and more karaoke machines than the year before—all paid for with money sent back by family members laboring in China’s cities. The biggest source of cash income in most villages I visited was family members who had migrated to cities, found work, and sent their earnings home. (In 2023, of course, the fear is that the massive numbers of spring travelers will also bring home COVID.)

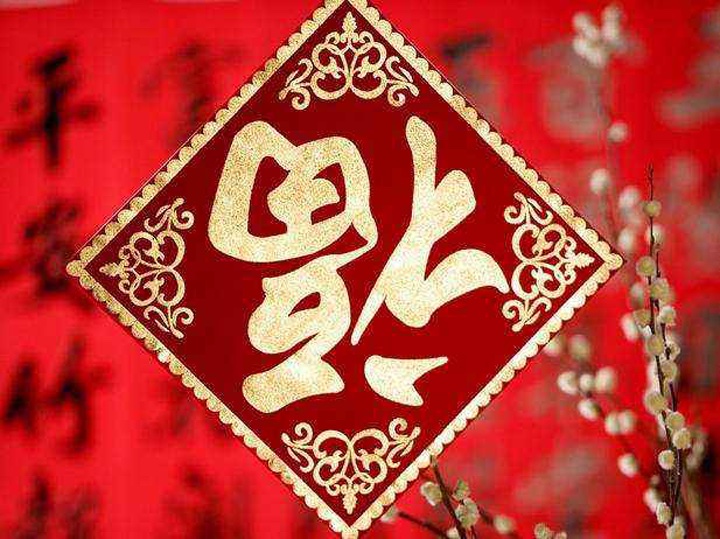

Homecomings were festive—village doorways had large, red paper characters pasted on them. In the center of every doorway were the characters 福 (fú “good fortune”) or 春 (chūn “springtime”), pasted upside down. When small children see the upside down characters they shout “good fortune is upside down!” or “springtime is upside down!” In Chinese, the word for “upside down” is 倒 dào. This is identical with the pronunciation of the word for “arrived” (到 dào). So the children’s cries of “Good fortune is upside down!” (福倒了 fú dào le) sound identical to “Good fortune has arrived” (福到了fú dào le). On either side of village doors are pasted duìlián 对联 or spring couplets, balanced seven character phrases with auspicious messages such as 八方财宝进家门,一年四季行好运 (From all directions wealth enters our door, in all four seasons of the year we have good luck) or 万事如意福临门,一帆顺风吉星到 (All things are as we wish and good fortune is at our door, everything is smooth sailing and our lucky star has arrived).

The Chinese language is rich with opportunities for wordplay, and this richness is most apparent during the New Year in rural China. In the southern provinces of Yunnan and Guizhou where I typically traveled, families eat glutinous rice flour cakes on the eve of the New Year. The sweet, tasty cakes are called niángāo 年糕, whose pronunciation sounds like 年年高 which means “every year is better than the last one.” Every family will eat fish on the Lunar New Year’s eve, saying “every year we have fish” (nián nián yŏu yŭ 年年有鱼) which sounds just like nián nián yŏu yú 年年有余 meaning “every year we have abundance.” In the north of China people eat dumplings or jiăozi 饺子 on New Year’s Eve, not only because they are delicious, but because they also illustrate yet another clever play on words. Historically in China, each day was divided into twelve separate two-hour periods or watches. The period from 11:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. was called 子时 or zĭ shí. On New Year’s Eve as midnight approached, the time changed to zĭ shí. The term jiăozi 饺子 or dumpling has a similar pronunciation with jiāozĭ 交子 which means that time has entered the two hour period of zĭ shí—when the day changes from New Year’s Eve to New Year’s Day. Also at midnight people set off unbelievable numbers of fireworks, often homemade. This was both deafening and dangerous. The villagers described it as rènao 热闹 (literally “hot and noisy”).

I always felt very fortunate to be able to spend the New Year with families who reunited in their villages—I learned a great deal about cultural traditions including language and food. This New Year, enjoy it with your children, whose teachers have shared with them many of the rich traditions of the Lunar New Year. As you enjoy dinner on the Lunar New Year’s eve January 21, ask them to teach you about the traditions they have learned in school. You’ll be surprised and delighted by how much they know.

Happy New Year everybody!